Equine Strangles

By Drs. Christopher Blevins and Mike Moore

Equine Strangles is a disease most often observed in young horses 1-5 years of age. The etiological agent Streptococcus equi subspecies equi is not a normal inhabitant of the equine upper respiratory tract. The S. equi organism is either inhaled or ingested after direct contact with mucopurulent discharges from affected horses or from contaminated equipment1.

History: A four month old, male, paint weanling was noticed to be having respiratory distress with both inspiratory and expiratory dyspnea on the evening of September 20th. According to the client, the foal was housed with approximately 25 other foals and some of these foals within previous days were breaking with what appeared clinically to be “strangles”.

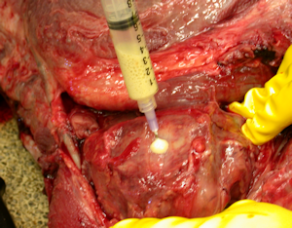

Clinical signs: Upon presentation to KSU-VHC the foal had marked inspiratory and expiratory respiratory distress. The foal had marked swelling of the submandibular and retropharyngeal lymph nodes and large swellings on both sides of the throatlatch. A quick TPR was performed (T:102.4, P:80, R:28) and a temporary tracheostomy was then performed. A nasal swab was submitted for culture. (Figure 1, affected foal from this case)

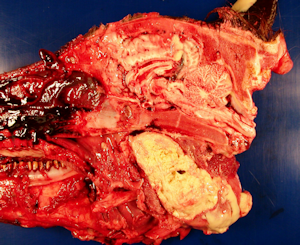

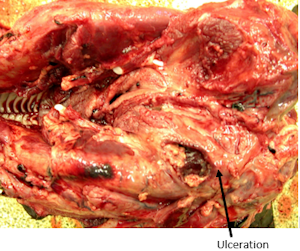

Diagnostics: Because of a grave prognosis, on September 21st the foal was euthanized and necropsied. Gross necropsy description included right guttural pouch was severely distended with caseous exudate. (Figure 2) The medial compartments of both guttural pouches were severely dilated with exudate. The ventral floor of the medial compartment of the right guttural pouch contained a full thickness ulceration. (Figure 3) The submandibular lymph nodes were severely enlarged but not draining. Bacterial culture of guttural pouch exudates yielded Streptococcus equi subspecies equi. (Figure 4)

Outcome: Once the disease was confirmed, the herd was closed from any horses entering or exiting the site until 30 days after drainage had stopped in the last case. The disease was allowed to run its course in this herd as no complicated respiratory issues were noted in the other horses on the farm. After the last case had resolved all stalls were stripped, the walls and buckets cleaned with a disinfectant, and the floors heavily limed.

Take home messages from this case: Any new horse coming into the herd should be tested for S. equi, equi based on nasal wash or swab of guttural pouches for PCR and culture. In addition, if Strangles is a concern on the farm, the new horse should be blood tested for M-protein titer for S. equi prior to vaccinating1. This will help in determining if an allergic reaction to the vaccine for S. equi is possible (Purpura Heamorrhagica). If the titer is low the new horse should have the two-shot series of strangles vaccinations before coming into the farm and you should still be aware that there is some danger of contamination from carriers that may still harbor the disease for months. The nasal swab from September 20th grew Streptococcus zooepidemicus, a normal inhabitant of the upper respiratory tract. A PCR request on this sample may have been an additional diagnostic test to assist with this case.

Prevention is best accomplished by quarantining any new additions to a herd for four weeks and screening for S. equi by repeated nasopharyngeal swabs or lavages1. This is difficult in most barns. An intranasal vaccine should be given at six months of age and boostered in three weeks. Annual boosters are then required. The immunity which this vaccine produces is not perfect, but it may prevent disease from casual contact and lessen the severity if they do get it.

|  |

Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|

|

| Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

Reference:

1. Streptococcus equi Infections in Horses: Guidelines for Treatment,Control, and Prevention of Strangles. J Vet Intern Med 2005;19:123–134