December 2018

Feet, Feet and MORE Feet

By Kelli Milsap, RVT

Over this last summer and fall we saw a large number of lame cattle admitted to the Veterinary Health Center (VHC) at Kansas State University. A majority of the cases involved feet, specifically subsolar abscesses or ulcers. Both can be caused by many different factors. These factors include environmental or metabolic issues, and foreign objects. The discussion below will focus on anesthetizing and examining a bovine foot to diagnose lameness.

If your clinic does not have a tilt table, you can easily examine the bovine foot in a normal squeeze chute. Wrap and tie a soft cotton rope around the leg above and below the carpus or tarsus. Take the other end of the rope and make a few good wraps around a solid, sturdy part of the chute directly above the leg you are picking up. Once you are ready to lift the leg, get the bovine to shift their weight off that leg. As soon as the weight is shifted, quickly pull on the rope to lift the leg. Once you have the leg lifted and securely tied off, the foot can be examined. A good reference describing this and other techniques is the book by Ballard and Rockett called Restraint and Handling for Veterinary Technicians and Assistants.

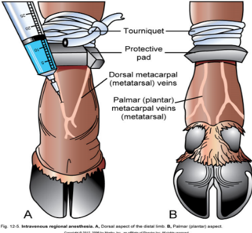

If an ulcer or abscess is present, we recommend that the foot is anesthetized to make the rest of the exam and treatment easier to complete, as well as to provide comfort for the patient. To anesthetize the foot, apply a tourniquet below the carpus/tarsus and perform a Bier (IV lidocaine) nerve block. The dorsal metacarpal veins and the palmar metacarpal (dorsal common digital) veins are easiest to access. (Figure 1)

Most commonly we use the dorsal metacarpal/metatarsal veins. The best place to locate these veins is in the crease on the front of the leg. (Figure 2) Important things to remember when anesthetizing the foot is to make sure to inject in the midline and always insert the needle at an almost 90° angle to the foot. A butterfly catheter (19 gauge or smaller) with a short extension, as noted in Figure 3 below works best. Inject about 20 cc into the vein (lessen the amount for younger, smaller patients); a bleb should not form and no syringe plunger resistance should be experienced during injection. If a bleb is observed during injection, the needle needs to be adjusted to make sure it is in the lumen of the vein. Allow about 5 minutes for the foot to be completely anesthetized before continuing with the examination and treatment.

|

|

|

|

Figure 1 (Photo: |

Figure 2 | Figure 3 |

There are many different instruments and tools a veterinarian can use to complete a lameness exam of feet. Hoof testers allow pressure to be applied to all areas of the hoof to pinpoint the location of the lameness. Sometimes the hoof tester will pinpoint the location of an abscess, as you will see the abscess material leak out of the sole defect. Make sure to not press on the coronary band with the hoof tester, as this will elicit a pain response. If a lesion location is detected, the veterinarian can then investigate the area using hoof knives (Figure 4) and/or rongeurs (Figure 5).

|

|

| Figure 4 | Figure 5 |

If the lameness is severe, placing a wooden block on the unaffected claw to shift the weight off the affected claw will allow for quicker healing and enhance patient comfort. When placing a block, it is key to make sure the block edges are even with the outside edges of the claw and toe.

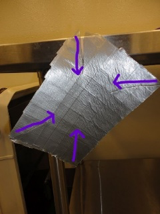

There are also times that the affected claw requires a bandage. Each veterinarian has their own preference on what bandage materials are used, but making sure to span the coronary band and assure the bandage is not too tight are key. Many times you may also need to place a duct tape “boot” over the bandage to make sure it doesn’t get wet or dirty. There are many different ways to make a duct tape “boot”. A boot can easily be formed by using 3 layers of duct tape layering them in opposite directions. After layering, incise each corner towards the center so it can be wrapped around the foot to form a tight seal. (Figure 6)

|

|

|

|

| Figure 6 |

In one case a cow was presented to the VHC that had stepped on a nail, causing a severe lameness. (Figure 7) We completed radiographs to assess how far the nail was imbedded and how much internal damage was present. Soft tissue swelling was extensive. (Figures 8 and 9) There was also a lateral displacement of the third phalanx and a septic coffin joint. (Figure 9) Additionally, an abscess had exited at the coronary band. (Figure 10)

|

|

|

|

| Figure 7 | Figure 8 | Figure 9 | Figure 10 |

Lameness can be a very costly disease for livestock owners. If intervention occurs early in the course of the disease, many times the animal can return to a productive life. When a lameness is left untreated or undiagnosed, the animal may become anorexic, lose weight, and develop arthritis. It is always best to examine a lame animal sooner rather than later.

Kelli Millsap is a livestock services nurse in the Veterinary Health Center at the Kansas State College of Veterinary Medicine.

Next: Concerns About Vitamin A Deficiency in Midwest Cow-Calf Herds this Calving Season

Return to Index