April 2023

Asian Longhorned Tick and Bovine Theileriosis

By Gregg A. Hanzlicek, DVM, PhD, PAS

|

|

Fig 1. Dorsal view of female Asian longhorned tick (USDA/APHIS) |

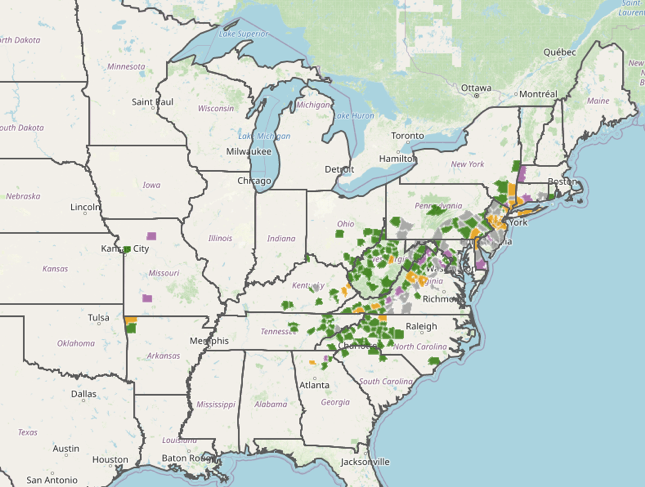

The Asian Longhorned Tick (also called the cattle, bush, East Asian or scrub tick), scientific name Haemaphysalis longicornis, has become established in the U.S. (Figure 1) Originally this tick was found in 2017 (probably has been in the U.S. since at least 2010) but was and now has been found in 18 states. (Figure 2) It has not been found in Kansas, but it has been reported in western Arkansas and Missouri.

The Longhorned tick can be found on most domestic animals including dogs, cats, horses, cattle, sheep and goats, and on a variety of wild animals including cervids, several bird species, raccoons and opossums. This tick is somewhat unique because it is parthenogenetic, and females can produce very large numbers of offspring in the absence of male ticks.

Longhorned ticks are not believed to be a carrier of Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease), Anaplasma marginale (Bovine anaplasmosis), Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Canine anaplasmosis). Experimentally, but not naturally, this tick has been able to carry Rickettsia rickettsia (Rocky Mountain spotted fever).

|

|

Fig 2. Locations where the Asian Longhorned tick has been identified (environmental and animal sources - USDA/APHIS) |

The primary concern with the establishment of Longhorned ticks is their role as the carrier of Theileria orientalis (Theileriosis) in cattle. All other known U.S. tick species are not known to carry T. orientalis, although some researchers believe black flies, sucking lice and needles can transmit this disease.

There are eleven T. orientalis genotypes in the U.S. and the world. Of those, only Ikeda and Chitose are pathogenic in cattle.

Theileria sporozoites produced by the female are transmitted during blood feeding on the host animal. Initially leukocytes are infected. Although infected, Ikeda and Chitose genotypes are not known to have any negative effect on these cells. Later, Theileria merozoites infect red blood cells. Similar to anaplasmosis, the infected cells are removed from circulation primarily by the spleen. Anemia, abortion, fever and weakness are typical clinical signs of acute infection. Most animals recover and become life-long carriers. Clinical signs can reoccur in carriers during times of stress such as late gestation, lactation and transport.

One of the most striking differences between A. marginale and T. orientalis is the difference in clinical signs age-of-onset. A. marginale clinical signs are typically only observed in adults (>2 years of age). T. orientalis associated clinical signs, including mortalities, have been observed in calves as young as 6-14 weeks of age. Another difference concerns treatment; T. orientalis appears to be very resistant to oxytetracycline.

Nonpathogenic Theileria genotypes have been found in U.S. cattle; it is important to distinguish pathogenic from nonpathogenic types during surveillance or case workups. KSVDL has developed a PCR panel (MDL-7130) that is specific for the two pathogenic Theileria orientalis genotypes (Ikeda and Chitose). Requesting this panel would be appropriate when investigating both acute and carrier cases. The appropriate sample is 1.0 ml of whole blood (purple top tube).

KSVDL is in the process of completing a surveillance study to determine the prevalence of Theileria orientalis in client submitted samples. We will present a summary of the surveillance data at the Kansas State University College of Veterinary Medicine’s 85th Annual Conference for Veterinarians. The in person/remote hybrid conference will be held on June 4-6th in Manhattan, KS.

For more information please visit the information page for the 85th Annual Conference for Veterinarians.

Updated: April 12, 2023